The Lie that Economists tell us.

Economist lied to us - money did not come first

When talking with an economist about money and its purpose, we always hear the same story:

"Before money, people lived in barter economies."

Money was invented to prevent us from exchanging goods for goods. In many economics books, we hear:

"Imagine living in an economy before the invention of money. If you'd like to buy new shoes, you must find something of equal value for the person who wants to sell those shoes. Without money, transactions would be extremely complicated."

What if I told you that barter economies never existed?

What if I told you that the story economists tell you about the invention of money is a lie? - Money did not evolve around free markets.

The Basic Story

The common idea is that people relied on barter economies before we used money. From an economic standpoint, it makes sense if you want to create the story that money evolved around free markets and that governments were not the inventors of it.

The story starts with families in small communities being self-sustainable. They can provide themselves with all the necessary supplies of food and goods they need for their daily activities. Adam Smith was not the first to describe this idea. Millennials before him, Aristotle described a similar (made-up) story in his book "Politics" that families produced everything they needed themselves, but over time. Specializations were required to cover the needs of a larger community:

“The first society is that of a family; afterward the union of several families in a village, and still later the union of villages in a common federation; this is the state.”

Aristotle, Politics, Book I, Chapter 2

“It is evident, then, that the first principle of association, the necessity of providing for the common interest, and the reciprocal help which men cannot supply for themselves, imply another principle also, namely, that of just distribution, and the existence of a common interest of which distribution is the effect or expression."

Aristotle, Politics, Book I, Chapter 4

What Aristotle is saying here is that people come together because they recognize that there is a shared or common interest among individuals. Certain needs and goals are better addressed in a group rather than individually. When people pass the point of self-sufficiency, specific needs and objectives emerge in society. These objectives are but are not limited to security, economic cooperation, and social order. Due to the specialization that emerges to cover particular needs, men cannot supply for themselves - they are not self-sufficient. In a community or society, mutual aid allows society to function more effectively, and responsibility should be distributed fairly and equitably. Each member receives their due share and is treated fairly by their contribution. This results in the need to allocate resources and benefits in a way that aligns with this common interest. The distribution becomes a reflection of the community's shared values and goals.

This all sounds remarkably similar to what we would describe as the invisible hand that steers the market.

Adam Smith builds on Aristotle's division of labor and describes the human propensity to exercise trade. It is important to note that economists want to adhere to the idea that markets should be free from government influence. To create the idea of free markets, economists argue that property, money, and markets existed before political institutions and were the foundation of human society.

Adam Smith was a proponent of John Locke's view that governments should limit themselves to the protection of property rights within society:

“The great and chief end, therefore, of men’s uniting into commonwealths, and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property.”

John Locke, Chapter IX - “Of the Ends of Political Society and Government”

With these arguments, Adam Smith created the idea around the "invisible hand" that steers the economy. Though interesting to note, Adam Smith mentioned the "invisible hand" only once in the Wealth of Nations.

In his work "The Wealth of Nations," Smith paints a picture where individuals, in seeking personal gain and security, naturally choose to invest in domestic industries and direct their efforts towards activities that maximize value. Although their intentions are not geared towards public benefit, the aggregate effect of their actions guides resources and markets in ways that foster overall prosperity. Much like a hidden force, the "invisible hand" symbolizes the unintentional harmony that emerges from the self-interested actions of individuals, ultimately enhancing the collective well-being of the society they inhabit.

The Illusion of Free Markets

Now, we understand the need for economists to create a harsh distinction between politics and economy. Economists want markets to remain free of political intervention. To create the argument for this distinction, the story of markets preceding governments and politics makes sense. But the idea that barter preceded the use of money has no basis, and the idea that governments were not the inventors of money seems far-fetched.

Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776, at a time when Columbus and Spanish and Portuguese explorers were scouring the world for new sources of gold and Silver. During their explorations, no one reported societies based on barter. Most societies were using some form of money, and most had some sort of government issuing this money.

Jean Michael Servet', a 16th-century Spanish theologian and economist, provided an alternative perspective, discussing that money was not a later development following a barter system but that it had been a part of early economies in various forms. He suggested that money emerged due to human ingenuity and the need to facilitate trade and not a response to the inefficiencies of barter.

Many economists consequently dismissed his views that needed the linear transgression from barter, money, credit, and debt. The main problem with the barter theory is the oversimplification and assumptions made in many economics textbooks. While barter played a role in some smaller contexts, there is no anthropological or historic prevalence for large-scale barter economies worldwide and in human history.

The current challenge for economists is to part with the viewpoint that credit and debt were a linear transgression from money systems that evolved from barter and come closer to the idea that governments played a major role in establishing money systems.

What came before money?

When thinking about credit and debt, one of the first things that comes to mind is the loan that we would need to buy a house. We want to buy a house and ask the bank for a loan. After checking if we're viable for the loan, we will receive the number on our account to buy the house.

So, by logical deduction from this simple example, most of us could think that for debt to emerge, money is necessary. But that's not the case.

Let's go back to the first writings in human history, the Mesopotamian cuneiform (~4000 BCE). We can see that writing was initially used primarily for pragmatic reasons to keep track of economic transactions and debts that have been incurred. These texts, which were mainly economic transactions, showed the use of credit systems that preceded the invention of coinage by thousands of years. The temple administrators developed a single, uniform system of accountancy, much of it still with us.

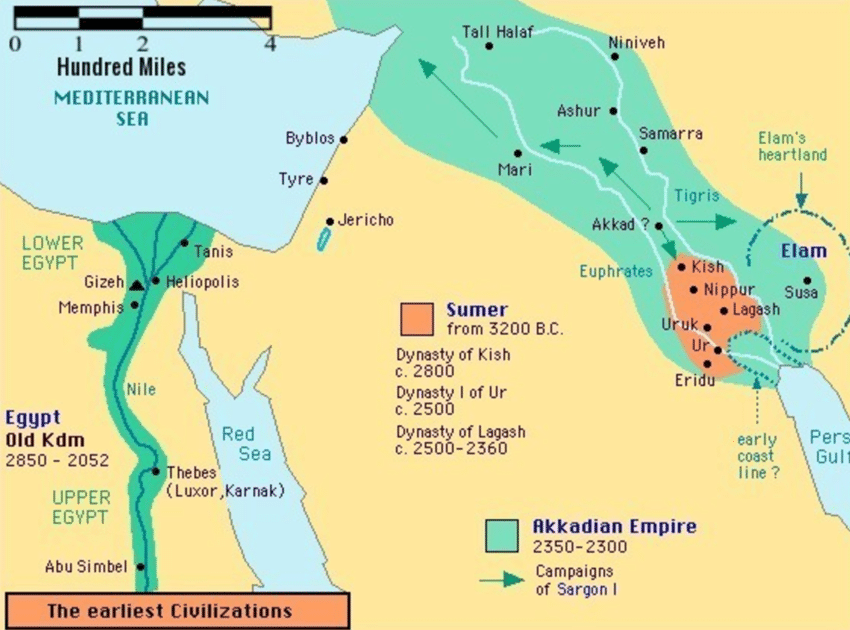

The Sumerians, those who lived in ancient Mesopotamia, had vast temple and palace systems. Sumer was in the southern part of Iraque and consisted of many individual city-states. Even though those city-states were mostly independent of each other, a centralized accounting system developed around the temple and palace system that embraced Sumer.

Those temple complexes were vast structures with priests, officials, craftspeople, and shepherds working in their states. Sumer lacked many important resources like stone, metals, and wood. They relied on trade to get those resources. To cope with the lack of those critical resources, they centralized much of the agricultural trade and developed systems to make the internal market more efficient.

Thanks to the Sumers, we have the 60-minute hour or the 24-hour day. Their basic monetary unit was a silver shekel that weighed one gur, or bushel of barley. The shekel could then be subdivided into 60 minas, corresponding to one portion of barley. The reason for the division of 60 minas was that Temple workers received two rations of barley every day, and with 30 days in a month, we can deduce the logic behind the division of a shekel.

In this sense, "money" was not the product of commercial transactions but the creation of bureaucrats to keep track of resources and move things back and forth between departments.

Now, for the most interesting part. While all the transactions, rents, fees, loans, and so on were calculated in silver shekels, there was no need for real Silver to move places. This does not mean that Silver did not circulate in the economy, but that due to the accountancy system, debt writings were the primary form of money moving around.

One reason Silver did not move much out of the reserves of the temples was that while debts were calculated in Silver, people could pay them off in pretty much anything they had lying around.

Temples were huge industrial operations that facilitated trade, which is why the fixed ratio of Silver to barley was of utmost importance. Indeed, most people paid off their debt with barley. But peasants could show up with goas, furniture, or anything else. The temples could process pretty much anything people brought them.

Even throughout the rest of the economy, with merchants or at inns, people did their transactions by running up a tab that would be settled during harvest time in barley or anything they had at hand.

The history of money is the history of debt.

To the economists' dissatisfaction and refutation of their story, debt and credit came before money.

The economists' story is backward. At the same time, they describe a linear transgression from barter to money to credit and debt. The truth is that debt and credit, or what we could call "virtual money," came first.

Knowing all this, economists tend to ignore these facts and create the story that if money disappeared, people would move back to barter.

The irony here is that we have many instances where an empire, kingdom, or government disappeared, and even with their disappearance, people would continue to rely on the previous - not in real existence anymore - currency system to measure transactions with debt and credit.

In 1936, Luigi Einaudi wrote a book called "La Moneta" in which he described the persistence of traditional denominations of currency such as pounds, shillings, and pence over a long historical period despite the changing nature of the actual coins in circulation.

In the 1600s, at least, actually called the old Carolingian denominations "imaginary money" - everyone persisting and using pounds, shillings, and pence (or livres, deniers, and sous) for the intervening 800 years, despite the fact that for most of the period actual coins were entirely different, or simply didn't exist.

Luigi Einaudi, 1936, La Moneta

The need for the actual coins was very low or even nil. What mattered more was that the people continued calculating their debts with the denominations they were most familiar with.

Why should you care about all this?

The most common definition of economics is "Economics is a science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses," as it was defined by Lionel Robbins in 1932.

When we mention the words "invisible hand," most people in modern society know that we're talking about Adam Smith's memorandum "The Wealth of Nations" and that it discusses each person's intrinsic desire to maximize their personal utility and that in a society where is everyone is utility-maximizing, it results in a system where resources are efficiently distributed, markets are self-stabilizing and don't require government intervention.

The history of money shows another side. We don't devolve to barter systems when governments collapse. Money is not the invention of markets but that of governments to control resources within an economy. Credit and debt did not evolve from money but are much older than money itself. Most societies lived on a credit and debt system; even more commonly, resources were shared, and people supported each other to make communities work.

We're living in a time where we take the capitalistic pillars for granted, and that our current system evolved quite a bit from those of a few thousand years ago, when, in fact, there were only a few significant revolutions in our money system.

We're limiting our imagination to our current capitalistic society and even adjusting history to support our beliefs and ideas.

I want the reader to realize that we should question what we take as ground truth, ignite our imagination, and challenge our beliefs on what systems could work in the future.